Denazification in Germany: exhibition at Allied Museum

UPDATE: This temporary exhibition ended May 31, 2016.

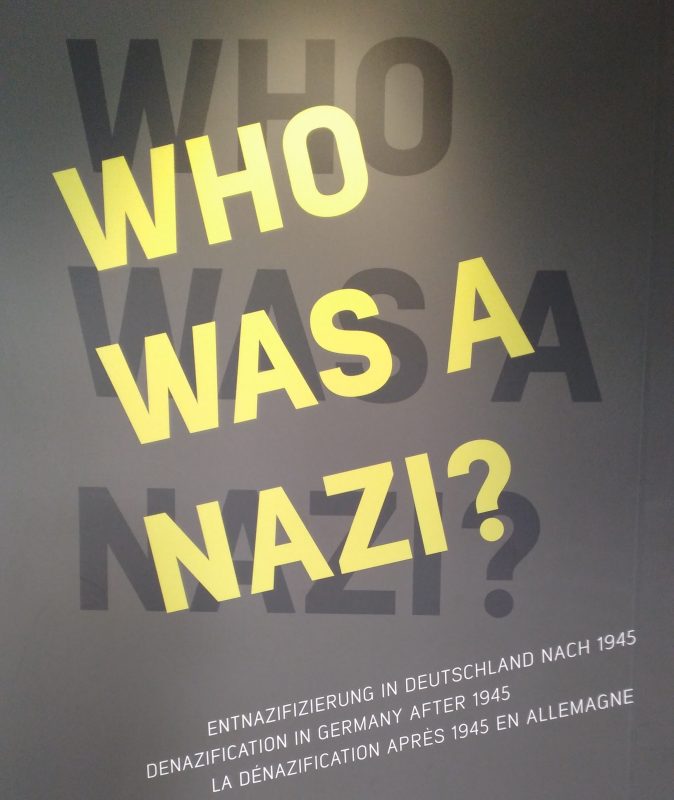

Recently, on a day off, I took the time to go to the Allied Museum to review the current special exhibition. The museum documents in its permanent exhibition the political history and the military commitments and roles of the Western Allies in Berlin. It’s current special exhibition is called: “Who was a Nazi?” and looks at the denazification process in Germany after WWII. Because the research done and information gathered are valuable for understanding the time and circumstances, following I have summarized the information given in this exhibition. (All information contained in this article is based on the exhibition at the Allied Museum).

Already at the Yalta Conference in 1945, the leaders of the Allied powers considered the necessity of some kind of denazification process for Germany after the end of war. The most well known measures were the “Nuremburg Trials” from 1945-1949. In 13 trials 209 defendants were charged with crimes against the peace and humanity as well as war crimes. Of these, 36 were handed the death sentence, 35 were acquitted and the majority of the remaining defendants received long prison terms. This exhibition, however, does not focus on Nuremburg but rather on how an entire society was put under political scrutiny: the process of denazifying the „average Hans“.

First, the exhibition mentions the enormous task of cleansing the public realm from Nazi symbols as the ideology had permeated every aspect of Germany’s day-to-day life. This not only meant banning the swastika as a symbol and removing it from Germany’s heraldic coat of arms, but also destroying millions of flags, disposing of portraits and sculptures of Adolf Hitler galore, replacing millions of documents and forms (those previously in use all showing the swastika), renaming streets, removing books from libraries and banning Nazi textbooks from classrooms.

The exhibition goes on to show the attempt to re-educate Germans by confronting them with the shocking atrocities of the Nazi regime. The idea behind these shock tactics was, on the one hand, to hasten the reeducation process, and, on the other, to counter any denial of the Nazi crimes and the Holocaust. The Allies compelled thousands of local residents near concentration camps to look first hand at the sites of the Nazi crimes. Germans were forced to unearth victims of the Nazi regime from mass graves and rebury them in cemeteries. In addition to these direct confrontations, posters and films about the atrocities were shown to the German public in an effort to reeducate. Many people reacted defensively to these efforts or showed little interest. This soon raised doubt among the Allies about the effectiveness of these strategies and led to their being abandoned by mid 1946.

The main focus of the exhibition is about the task of identifying and detaining Nazis, investigating war crimes and purging former Nazi party members from sensitive professions. For a truly new beginning for Germany, it was deemed imperative to replace the Nazi elite in political and social positions by people not tainted in any way with a Nazi background. This meant dismissing Nazis from any position of responsibility in society. Nobody knew for certain how many active supporters the Nazi regime had had and whether enough democratically minded people could be engaged to ensure political stability. Millions of Nazi party members had to be found and categorized. The Nazi party (NSDAP) had some 8.5 million members and many millions more belonged to affiliated associations and organizations. The task was a political cleansing on an unprecedented scale.

At the end of the war the Allies initially arrested functionaries, SS and Gestapo members, and some civil servants. They were all sent to internment camps. This form of detainment, done without any due process, was known as „automatic arrest“. Between 1945 and 1950, more than 400,000 Germans were interned in this way.

In the Soviet zone, critics of the Soviet-style restructuring of the economy and society were also subject to arrest. Some 44,000 of the 154,000 Germans held in Soviet special camps died – a much higher mortality rate than in the camps in the Western zones. With the closing of the special camps in 1950, over 3,300 former internees were sentenced to prison terms or to death in the „Waldheim trials“, sham trials lacking proper legal procedures, conducted by the East German authorities.

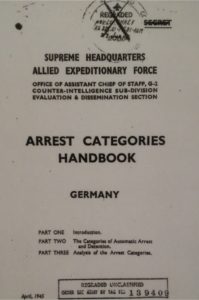

In the spring of 1946, the process of investigating individual responsibility began, both for Germans inside and outside of internment camps. Guidelines for this process were laid out in an Allied Control Council directive. It set up five classifications of individuals – „Major Offenders, Offenders, Lesser Offenders, Followers, and Persons Exonerated“.

Without the successful completion of this denazification process and an assigned classification, an individual had no job prospects. The process was based on a questionnaire, first developed during the Allied invasion of Italy, which eventually contained 131 questions. Despite the joint guidelines, in practice there were variations in the denazification procedures in the four occupation zones. The British developed their own questionnaire as did the Soviets.

In many cases people added exculpatory declarations by friends, neighbors and work colleagues to the questionnaires in an attempt to „whitewash“ their possible guilt. By contrast, incriminating documents and testimony were often missing, making it difficult for the tribunals to get an accurate picture of an individual’s actual responsibility.

Shortly before the war ended, the Nazi party ordered its membership file and other personal files to be destroyed. 20 trucks brought tons of documents from Nazi headquarters to a paper mill in Bavaria. But the mill’s director blocked the pulping and, in May 1945, informed the US military government in Munich.

It was not until October that the Americans realized the significance of the cash and took it to Berlin-Zehlendorf. This was to become the 7771 Document Center. The files included index cards for some 80% of the ca. 8.5 million Nazi party members, as well as files on members of Nazi organizations such as the SS or the SA. It was an immensely valuable resource for the denazification procedures.

During the most intense phase of denazification, between 1946 and 1948, the Document Center received up to 5,000 inquiries per day. At the time, only the military governments of the occupying powers had access. Later it was also passed on to the German tribunals. The Americans, British, and French made extensive use of the archives. By 1948, the Soviet military government had not made a single request for information to the Document Center, which was run by the American military government.

In addition to the enormous task of denazification, the country’s basic services and supplies had to be restored, new infrastructure had to be built. The country was faced with a host of problems: widespread destruction, a lack of food and accommodation, millions of foreign forced-labor workers, and incoming refugees from the former German territories, seized by various other countries. Given the difficult nature of these tasks, the Allies soon decided to involve Germans in the complex denazification procedure and transferred it to German tribunals called „Spruchkammern“. The dilemma was that many of the skilled workers needed for the onerous tasks at hand could also be found to be implicated in the Nazi past. As a result, a number of people who would otherwise have been ousted from their positions came away scot-free.

The occupying powers were already seen to use pragmatic approaches in various forms of amnesty to constantly reduce the number of people assessed for possible Nazi ties. Particularly in the case of people with specialized scientific skills, whom the Allies often recruited for their own purposes, they would tend to waive denazification procedures. Other professions also benefited from that practice. In the British occupation zone, for instance, food shortages were so severe that the authorities soon waived denazification for the agricultural sector.

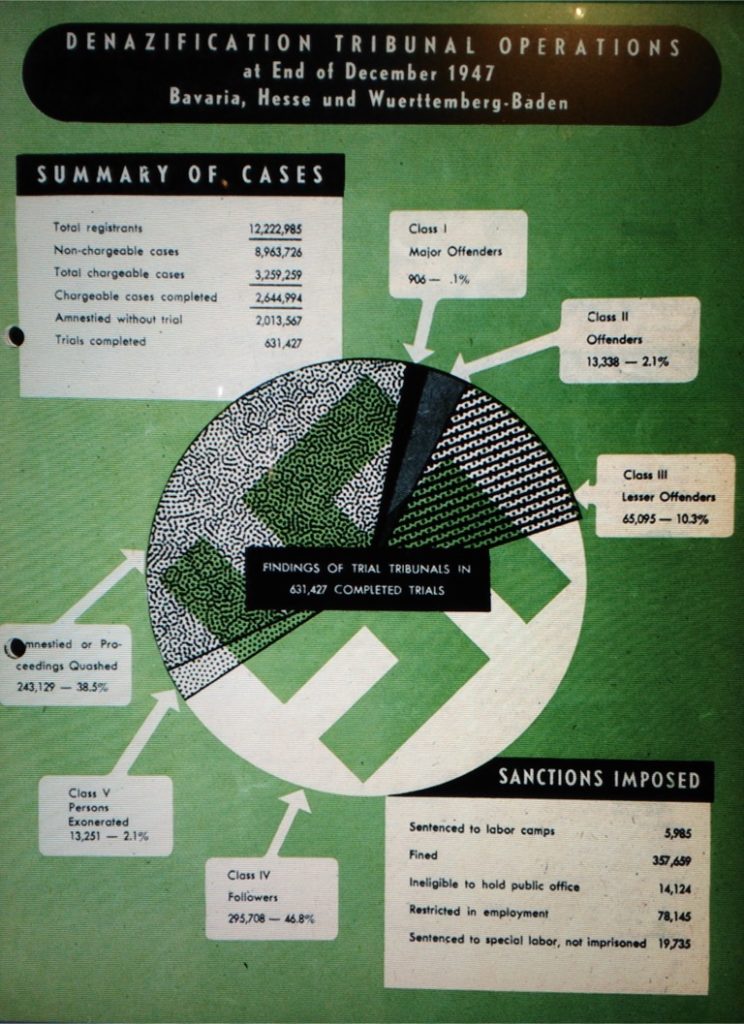

In addition to transferring responsibility for denazification to German authorities, the fact that elections were held in the regional states in 1946 was a clear sign that the Western Allies trusted in the possibility of a new beginning for German society and politics. It soon became standard to classify people as “Followers”. By the end of 1947 a mere 1% of those who underwent denazification procedures could expect prison sentences or even lasting disadvantages because of past involvements. The Americans accepted this development despite the fact that it contradicted the original idea of political cleansing.

The Soviet military administration announced that denazification would end in the Soviet zone on March 10, 1948. The Western occupying powers reacted by transferring jurisdiction over the ending of denazification to the German state assemblies. Thereby the Allies withdrew entirely from the process they had initiated with such vigor three years earlier. In May 1951, the Bundestag (German Federal Parliament) passed a law allowing all „Lesser Offenders“ and „Followers“ to return to the Civil Service. On July 1st of the same year a law officially ending denazification took effect.

Altogether, in the Western zones about 3.6 million cases had been heard, with another 200,000 in Berlin. Less than 0.7% of the subjects had been placed in the top two categories „Major Offenders“ and „Offenders“. The bulk of Nazi party membership had emerged from the denazification procedures as „Followers“ or even „Persons Exonerated“. In the Soviet Zone some 520,000 former Nazis had been fired from their jobs and banned from key positions in government, the judiciary, and police forces.

In the end, the objective of removing all former members of the Nazi party (NSDAP) from positions of responsibility and society failed, not least because the political will to enforce this objective had waned. For both the occupying powers and the Germans on both sides, the Berlin Blockade and the founding of two separate German states symbolized the start of the Cold War, with priorities significantly shifted.

Despite the fact that the hoped-for complete purge of the Nazi elite did not happen, dismissals and arrests of former Nazi functionaries did at least have a lasting effect on politics. After 1945, Nazi ideas found no ground, either as an ideology or in a political party and have remained marginalized up to the present day. And perhaps that was the most important thing denazification could and did achieve. The same German society that produced the Nazi regime, established, within just a few years, the new Federal Republic of Germany, a stable democracy of more than sixty years, supported by a broad majority of the population.

If you would like to visit the Allied Museum on your Berlin Cold War Tour one of our private guides will be happy to take you there. Even though situated outside the city center and not one of the overcrowded sites, our car tours makes it perfectly easy to get there and can combine it with other sites of the former American sector.

Posted by our guide

Lars Jokubeit

No Comments